New Science's Report on the NIH, now with more visuals 🎉✨

Introduction

In 2006, the National Institutes of Health Reform Act passed Congress. 1 This droll, political document established a Scientific Management Review Board within the NIH. That board — comprised of Dr. Anthony Fauci, a former Lockheed Martin CEO and high-ranking NIH officials — was tasked with issuing recommendations for NIH reform; a noble and useful purpose.

The board has not held a meeting since July 2015 and has written just eight reports in total, all of them between 2010 and 2015. The committee, staffed by high-ranking officials and with th power to identify flaws and encourage reforms in the NIH, has quietly gone defunct.

That should be concerning, in part, because the NIH is a behemoth institution with an annual budget of $42.9 billion in 2021 and $51.96 billion in 2022. It consists of 21 institutes, 6 centers and 300,000 current grant recipients and spends about ten times more on bioscience than the next highest-spending government agency (the European Research Council 2) and more than the entire government spending for about two-thirds of the world’s countries.

It spends 20 times more on biomedical research, per year, than the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. 3 And yet, it does not have a functional internal board to offer feedback or propose reforms.

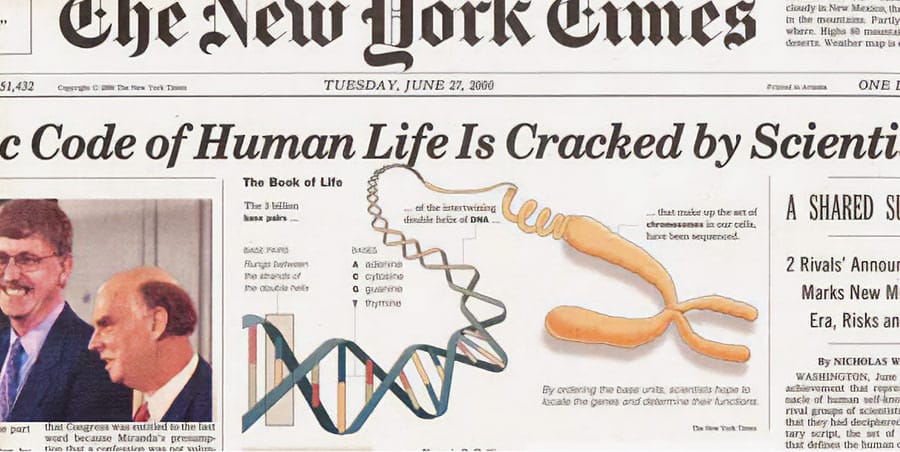

The NIH is the foundational engine of modern bioscience and has contributed to countless breakthroughs, even in a purely modern context — just look at the Human Genome Project and mRNA vaccines.

Currently led by Lawrence Tabak, the NIH was formed in 1930 under the Ransdell Act as The National Institute of Health. It was given a single mandate: promote public health through funding internal and external research into biomedical domains.

Research activities at the NIH are still divided into two categories: intramural and extramural. Intramural research, which constitutes 10-12% of the NIH’s annual budget, is conducted in NIH labs on NIH property by NIH employees and contractors. Currently, there are over 5,000 individuals conducting intramural research, including 1,200 principal investigators and 4,000 postdoctoral fellows.4 Extramural research is carried out by universities, non-profits, hospitals, and companies with NIH funding that amounts to around 80% of its annual spending. Roughly two-thirds of this extramural spending goes directly to 300,000+ researchers5, while the remaining third goes to host institutions to reimburse their expenses related to government-funded research.

In its 90 year history, the NIH has largely staved off politicization; its inflation-adjusted budget has gone up 52% over the last 30 years. Support for government-funded research regularly polls in the high 70 to 80 percent range.

Although the NIH is a division within the larger Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), its funding is determined independently by Congress. Since 1938 (the earliest year with financial data), the NIH’s annual budget has decreased only six times.

Tens of thousands of people benefit from the NIH through employment. Hundreds of thousands of researchers at universities, private labs, and companies benefit from the NIH through grants. Hundreds of universities, including nearly all of America’s most elite universities, also benefit from the NIH through grants, a large portion of which (more than $10 billion per year) goes straight to those universities and subsidizes their facilities. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies benefit from the NIH by generating basic research, which they then turn into intellectual property and marketable products. The general public benefits from the NIH by reaping the benefits of bio-scientific advancements.

It’s not surprising, then, that few people march in the street to reduce the NIH’s budget. No politician campaigns on cutting funds for Alzheimer’s research. Private industries, non-profits and interest groups don’t have a concerted interest in fighting the NIH, which ostensibly exists to promote public health, and is ultimately answerable to the American people.

While this popularity can be seen as evidence of its success, we should also recognize the perils of the largest research organization on earth being a government bureaucracy with overwhelming support and virtually no opposition.

The NIH’s extramural research is systematically biased in favor of conservative research. This conservatism is a result of both institutional inertia, concerns by the NIH leadership that the organization could lose the support of Congress, and efforts by NIH beneficiaries to maintain the status quo.

The extramural grant distribution process, which is run through peer review “study sections,” is badly in need of reform. Though there is considerable variability among study sections, many are beset by groupthink, arbitrary evaluation factors, and political gamesmanship.

The NIH may be hamstringing bioscience progress, despite the huge amount of funds it distributes, because its sheer hegemony steers the entire industry by setting standards for scientific work and priorities.

Most problematic, the NIH is highly resistant to reform. Many proposals have been shot down during discussion phases, or scaled back before implementation. The NIH’s own internal review board has been inactive since 2015, as mentioned at the start of this report section. Still, many of the NIH’s problems are likely a natural product of being a $40 billion+ per year government bureaucracy.

Many of the NIH’s problems are likely a natural product of being a $40 billion+ per year government bureaucracy.

To understand this duality and the inherent complexity of the NIH, I interviewed 41 people and had more informal discussions with about half a dozen more while drafting this article. Eleven sources formerly or currently work in the NIH intramural programs, 24 currently or formerly received extramural funding, 18 currently or formerly served on or ran study sections, five held leadership or advisory positions at the NIH, and six held leadership positions in other bioscience research funding institutions.·

I did my best to talk to a wide range of people, spanning mainstream and heterodox positions. Some interviewees had decades of experience with NIH funding, while others left scientific research partially out of a dissatisfaction with academia.

Every person that I interviewed was granted anonymity. Despite that promise, quite a few said, during the interview, that they would be concerned about their jobs or ability to get a grant from the NIH in the future if they were publicly attached to a criticism of the NIH. One interviewee referred to a “fortress mentality” within the organization.

A few also stated that, regardless of how much I guaranteed anonymity, many researchers would refuse to talk to me because the risk was too great. One interviewee asked three other researchers to talk to me, and all three declined explicitly on these grounds.

This is concerning, in part, because the NIH undoubtedly has flaws, it is drifting away from basic research, and it is in clear need of reform.

Through my research, I have attempted to establish a comprehensive evaluation of the NIH. My objective is to both present a synthesized consensus of views on the NIH and its many components, and to present dissenting views, especially since many issues at the NIH have provoked mutually incompatible stances on how to improve operations.

My goal is to understand what works and what doesn’t work, the nature of the NIH’s incentive structure, where the organization can most be improved, and how the NIH impacts American and global bioscience.

I admit that despite the length of this work (33,000 words), I have not covered everything about the NIH. I did my best to broach every interesting topic, but based on feedback from reviewers, I know I have left plenty unsaid; especially the NIH’s impact on scientific journals and publishing. Hopefully others will build on what I have written.