Part 1: Big Picture

The NIH is Highly Regarded

I think the key issue in this large-scale assessment is quality vs. quantity. Has the NIH pushed global science forward because it has funded so many great researchers? Or, because it has so much money, is it pretty much impossible not to fund great researchers when the vast majority of that money gets pumped into elite research institutions?

With a few exceptions, all interviewees agreed that the NIH funds lots of good research and has been invaluable to global bioscience progress. Many praised the government’s role in providing funding to so many researchers for over half a century. One interviewee said he “has a tremendous love for the NIH.” Another interviewee, who was born overseas, said the NIH is “part of what makes America great.”

NIH is “part of what makes America great.”

When asked whether the NIH’s budget should be increased, decreased, or remain the same, nearly all respondents supported increases. Most commonly, they supported a doubling or even tripling of the NIH budget. Even many of the more critical interviewees supported budget increases. I would rate only five interviewees as net-negative on the NIH as a whole, none of whom had long histories of interactions with the NIH. All emphasized that the NIH’s policies created incentives that rendered its research overly conservative (in an institutional sense), too concentrated in top-level institutions, and likely slowed bioscience research on the margin.

The NIH Is Vital to Careers

Attaining an NIH grant is nearly essential to having a career in bioscience.6 One interviewee called it the “bread-and-butter” of research, while another called it the “lifeblood” of bioscience research. Multiple interviewees noted that universities de facto require the attainment of multiple NIH or comparable federal grants to become professors and attain tenure.

This trend is driven more by economics than anything else. NIH grants are more numerous, pay higher amounts, and last longer periods of time than any other bioscience grants given by the public or private sector. Or, rather, NIH grants have the combination of all three of these qualities, whereas other top institutions only have one or two of them. For instance, there are grants that provide equivalent amounts of money and (often more) time, like from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), but these are far less numerous and therefore harder to get. While most extramural NIH grants have above a 20% chance of acceptance (including multiple submissions), the HHMI approves fewer than 1% of grant applications.

Thus, if a biomedical researcher was, for some reason, highly motivated to get adequate funding for a major project without NIH help, he would probably have to cobble together numerous grants from other foundations, which would likely require even more work than the NIH’s notoriously bureaucratic application process. And even if this could be accomplished, many interviewees noted it would come with significant career penalties.

Non-profit institutions pay lower indirect cost rates than the NIH, so universities tend to discourage them (more on this later), while money from private companies is considered inherently suspect within academia due to the potential conflicts of interest.

For better or worse, the NIH has a quasi-monopolistic position in the bioscience grant market. I asked numerous interviewees if this trend has a crowding-out effect (i.e. other grants have less demand or are altered in some way by the prominent position of the NIH), and most said that there was no crowding-out. Virtually all NIH grant recipients also apply for other grants, and most end up with secondary grants to support their NIH grant.

A few interviewees were strong dissenters and argued that the NIH had a “warping” effect on bioscience. One claimed that the central importance of NIH grants likely caused the protocols of other grants to adapt to NIH standards, both in an explicit structural sense, and in broader research priorities. After all, researchers have finite time, so they are likely to base their own research priorities around the aims of the largest grant recipient. This gravity well may have shaped the entire bioscience industry, again, for better and worse. Based on my own research, I’m inclined to agree with this stance, especially given the incentives created by the NIH for universities.

Because the NIH’s position in the bioscience industry is so hegemonic, it is incomparable to anything else, except maybe the European Research Council (ERC). You can’t ask, “does the NIH fund research more efficiently than the Howard Hughes Medical Institute or the European Research Council?” because the NIH spends 40X more per year than the HHMI and 10x more than the ERC. And, as one interviewee put it, “there is no Stanford in Denmark”.

Because the NIH is incomparable to any other existing organization, it’s extremely difficult, if not impossible, to accurately evaluate its efficiency level. This is crucial to understand this piece and the NIH as a whole.

Things could be, or already are, getting worse over time. Without any real competition, properly incentivized oversight or countervailing forces, no matter how inefficient it gets, the NIH will not go out of business, and is extremely unlikely to lose significant funding given the popularity of government-funded research and the support of major stakeholder beneficiaries.

The Boom Decade

From 1993-2003, the NIH’s budget increased 164%, rising from $10.3 billion to $27.2 billion.7 For comparison, in the same time frame, the Department of Defense’s budget increased by 39%,8 the Department of Agriculture’s budget increased by 17%,9 10 the Department of the Interior’s budget increased by 14%,11 12 and the entire federal budget increased by 53%.13 Even the National Science Foundation only had a 95% increase.14

I think this Boom Decade had a much larger impact on the modern NIH than its proponents at the time realized. The short-term euphoria of scientific expansion may have induced distortionary effects on the NIH and bioscience research industry, which are responsible for many of the issues outlined in this paper.

Post-Boom Decline

Roughly 80% of the NIH’s budget is spent on extramural grants given to institutions outside the government. And about 80% of that extramural spending goes towards research conducted in universities. 15

Thus, through the NIH, the federal government rapidly injected an enormous amount of cash into the university and private lab system – tens of billions of dollars over a decade with expectations of steady, if not increasing, funding in the future.

This massive infusion pushed the American research university system into an expansionary phase by incentivizing the construction of more laboratories and the hiring of more researchers and administrators to increase the capacity to earn even more NIH money. But then, in 2004, the NIH budget grew by a measly 3% and then basically flatlined in nominal terms from 2003-2015 (or shrank in real terms).

Universities and the bioscience industry had undergone too much expansionary momentum to adjust for this sudden halt in spending growth.

Thus, a mismatch in supply and demand formed. The number of bioscience researchers and labs continued to rapidly grow, just as they had done during the prior decade, but the federal research-driven demand stopped growing.

This mismatch may be responsible for many of the NIH problems outlined in this essay:

- The NIH is widely considered to be “underfunded,” despite currently being at its highest funding level ever in both nominal and real terms (albeit only recently in real terms).

- The fierce competition felt among NIH grant applicants may be a product of universities expanding their research capacity during the Boom Decade beyond what the NIH extramural budget can reasonably fund.

- As a result of that increased competition, study sections – the groups that evaluate NIH grant applications – have become more political and arbitrary.

- The rapid growth of the NIH’s budget gave it a quasi-monopolistic position in the bioscience industry, causing a gravity well effect whereby other institutions began adopting their practices and standards to the NIH.

- The universities may have gotten “addicted” to the influx of federal funds, and adapted their operations based around absorbing more federal money.

- The boom and bust may have strengthened the entrenched interests (i.e. the individuals and institutions who best capitalized on the boom) and then solidified their power since the money influx stopped suddenly after it had already been absorbed by the entrenched interests with little room for new players. This could have played out on the institutional level through universities building up huge research capacities, and at the individual level by prominent researchers amassing many large grants.

- Study sections and the NIH in general may have become more risk-averse in the dispersion of their funds now that there are so many institutional beneficiaries with entrenched interests.

Nearly all of my interviewees advocated for increasing the NIH’s budget, and many suggested drastic increases. If the 1990s and early 2000s are a good indicator, then a massive increase in the NIH’s budget could provoke the same effects again: a boom and bust cycle that, ultimately, results in unsustainable university expansion, a brutal job market for young researchers, and a less efficient NIH as an engorged bioscience research industry grows past its demand.

Entrenched Interests

Ideally, the NIH would fund research in a manner that maximizes potential long-term scientific progress within the bounds of its budget and power. But the NIH is a government-run organization and is naturally beset by political pressures that distort its structure and spending priorities.

Universities, research institutions, and major non-profit advocacy groups engage in lobbying, political pressure, and backdoor channels to push for NIH expansion, direct NIH funds toward preferable ends, and control NIH policies for their financial benefits.

Combined, these factors doubtlessly impact NIH operations and push it away from being the ideal, objective steward of taxpayer money. As far as I can tell, the NIH leadership does its best to support optimal research priorities (or at least what they perceive to be optimal), but the NIH is a government institution and is inevitably subjected to political forces.

While a few interviewees had a strong sense of this political distortion narrative and consider the NIH to be thoroughly compromised by special interests, the majority disagreed. From their point of view, although outsized benefits go to relatively few individuals and institutions, this may very well be the optimal distribution for the sake of efficiency because these entrenched interests are legitimately the best marginal researchers.

Institutional Conservatism

The single most consistent criticism of the NIH that I heard from sources, across all issues, was that the organization is too “conservative.” That is, too conservative in an institutional sense, not an ideological sense.

The NIH is considered insufficiently willing to take risks.

The NIH is considered insufficiently willing to take risks. This can be seen in its consensus-based grant evaluation, the de facto discouragement of ambitious grants, its drift away from basic research, and the lopsided distribution of grants which favor large, established organizations and researchers.

But the conservatism is most strongly felt in the NIH’s resistance to reform efforts. Throughout this essay, I’ll describe many critiques of aspects of the NIH’s operations, and I’ll describe even more proposed reforms. Yet, while reform discussions are common in and around the NIH, actual implementation of reform is vanishingly rare. The study sections, the grant protocols, the indirect cost system, and so many flawed aspects of the NIH have barely changed over the last thirty years. Most of the few reform efforts that have been implemented have failed or were scaled back, as I’ll demonstrate with the Grant Support Index and New Generation Researchers Initiative.

And, as mentioned, the NIH’s own Scientific Management Review Board, tasked with suggesting reforms and improvements, has not held a meeting or published a report since July 2015.

Francis Collins

Francis Collins was appointed director of the NIH in 2009. Before that, he led the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) within the NIH for 15 years. In December 2021, Collins stepped down from the directorship and took over a lab in the NHGRI.

With a 12 year reign, Collins is the Franklin Roosevelt of NIH directors. Most NIH directors come and go with the changing political winds, and they rarely survive new administrations. So how did Collins manage to stay in power for so long?

Seemingly, he survived by being the extremely rare individual who perfectly threads multiple needles in a niche, political realm. Namely, Collins is a progressive with a strong scientific background whose scientific viewpoints align with mainstream, left-of-center opinions on key issues, such as evolution and stem cells.

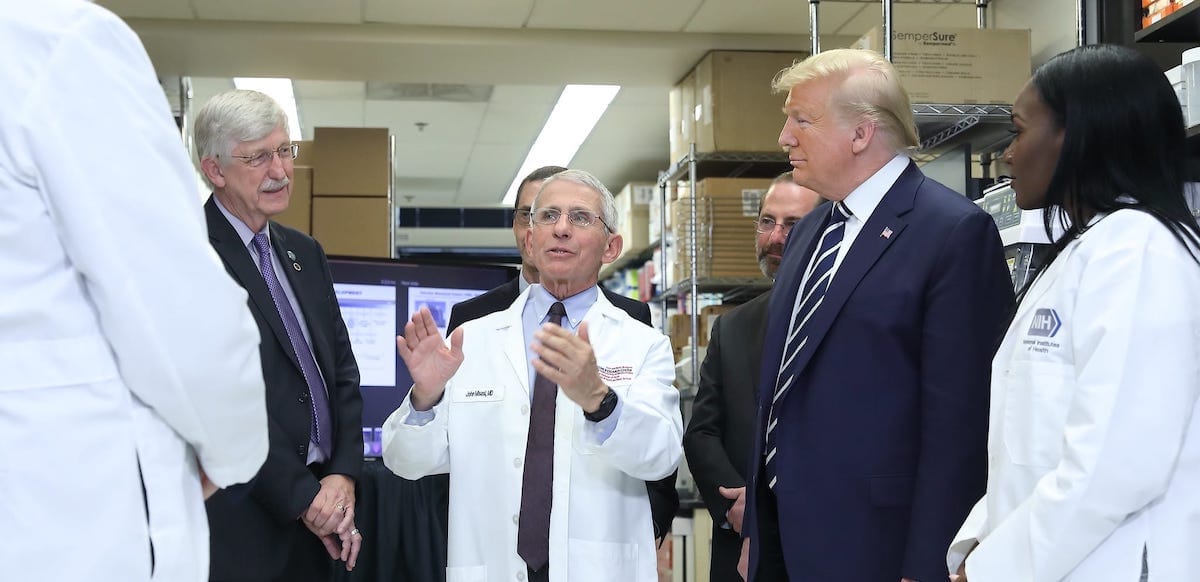

But Collins is also an outspoken, born-again Christian who literally wrote a book on how to merge science and faith. He is personally uncomfortable with abortion, but doesn’t want it outlawed. 16 He is the perfect combination of the political left and right in the realm of science. A few of my interviewees talked about Collins and at least one knew him personally. Their evaluations were almost universally positive, especially on a character level. One interviewee said Collins did a “spectacular job” and saved the NIH from massive budget cuts threatened by President Trump (a 18% budget cut was proposed, but was never enacted by Congress). Others were quick to praise his hard work, charisma, and general competence.

However, there were two recurring descriptions of Collins which many would consider criticisms. First, he was often described as “conservative,” again not in an ideological sense, but in an organizational sense. Second, he was often described as more of a politician than a scientist, at least during his tenure as director.

Combined, for better and worse, the perception is that Collins took a defensive leadership posture designed to protect the NIH, and he did so quite successfully, having finally guided the NIH out of its 12 year budget slump and then stopping President Trump’s two proposed budget cuts. But to achieve these goals, Collins may have sacrificed some of the NIH’s efficiency, dynamism, and long-term potential.

One of my interviewees was a former high-ranking official of the NIH, who says they personally know Collins quite well. They praised many of Collins’s personal characteristics, but said he is “not visionary” and “doesn’t like advice.” This interviewee blames Collins for orienting many NIH policies (peer review structure, grant structures, grant types, etc.) around big institutions and translational research, and away from high-risk experimental research. They identified at least one major instance where Collins crushed an attempt by an outsider being brought into the NIH to restructure its grant system to spread funds to smaller labs. In other words, Collins either encouraged or permitted many of the biggest criticisms I heard from other interviewees, possibly as a means of currying favor from the NIH’s largest beneficiaries so they would protect the NIH.

However, this interviewee and many others noted that being the director of the NIH is an extraordinarily difficult job, which necessarily involves making compromises between multiple factions and facing constant scrutiny from opportunistic critics.

For instance, one of Collins’s biggest controversies throughout his tenure was not an increasing shift away from basic research or the failure of the Next Generation Researchers Initiative, but his approval of a $3 million grant to the University of Pittsburgh, which involved grafting fetal tissue onto mice. That sum of money is nothing to the NIH budget and I doubt Collins had any personal input into the grant approval, but nonetheless, it was a lightning rod for his career and courted a flurry of attacks from politically conservative forces. He was called a “national disgrace;"17 anti-abortion groups called for his resignation.18

Collins left office in December 2021, but his influence certainly isn’t gone. His successor, Lawrence Tabak, is a long-time lieutenant. Collins still works in the NIH, and was appointed the scientific advisor to President Joe Biden.