Part 6: Intramural Research

The NIH’s intramural program is highly regarded. It was portrayed by many interviewees as one the best places in the United States to conduct bioscience research; they said it is “encouraging of innovation,” “very nourishing,” “an incredible concentration of both talent and ideas.” Another interviewee said that they received “unprecedented support” for an ambitious project that would have taken “10 to 20 years” to get started at a university.

Private industry has a profit motive that discourages basic science research, academia is rife with politics and career climbing, and private foundations often don’t have enough resources to pursue transformative work. But the NIH’s intramural program has a massive budget; researchers are given nearly complete freedom to pursue ambitious projects. And while extramural researchers probably get more raw funding, a dollar in an NIH lab goes a lot further than a dollar at a top research university, and thus NIH researchers are most likely better-funded in real terms.

Much of this research freedom is derived from the intramural program’s streamlined review process.

To become a researcher at the NIH, most people are selected through an application process. Reviews are done internally, by NIH personnel. Once hired, a researcher is given a budget, staff, and a lab in NIH facilities. They can work on almost any project for the next four to five years. After that time, a site review occurs, during which the researcher retroactively justifies their use of funds and outlines their research progress. One interviewee described this process as being narrative-oriented; intramural researchers often must connect and talk about multiple, disparate research projects.

If approval is granted after this site review, the researcher’s budget is replenished and they can continue working for another four- to five-year term. Theoretically, this process is indefinite. Some internal NIH grants also allow a PI to leave the intramural program to work elsewhere for a set period of time, with guaranteed extramural funding for a few years.

The NIH intramural programs often receive applications from the best postdoctoral researchers, according to several interviewees, because of this research freedom and minimal bureaucratic overhead.

NIH Salaries are Not Competitive

Given the above, why doesn’t everyone want to work at the NIH?

Because NIH intramural pay is mediocre to terrible compared to anywhere else.

A new intramural NIH researcher’s (PI's) salary is typically in the $140,000 to 180,000 range, depending on the specific institute. The ceiling for most researchers is around $220,000, though some can push a bit above $300,000 if they generate income through cuts from intellectual property royalties.98

The NIH is located in Bethesda, Maryland, a suburb of Washington D.C. In 2019, Bethesda’s median household income was $164,000 (2.5X the national median) and the median house value was $911,000. 99 Its county, Montgomery County, is the 18th wealthiest in America. This actually makes it one of the poorer D.C. suburbs, since four of the ten wealthiest counties are nearby.100 101

After ten or more years of intensive schooling, a salary of $150,000 in one of the most expensive parts of America is a tough sell. Many excellent researchers consider it too big of a sacrifice, especially as they get older and, potentially, start a family.

NIH intramural researchers are often highly qualified, and so their academic options, too, are elite.

Another option for bioscience researchers is to enter the private sector. One source, who used to make about $180,000 as an NIH researcher, consistently found jobs at private medical practices that offered more than $500,000 per year.

This experience was comparable for two other people that I interviewed. One source, who largely lauded the NIH, recently left their intramural program because the pay was not enough to support a family.

If a researcher is willing to forgo significant money for the sake of working at the NIH, then they are likely to be genuinely committed to scientific progress. In other words, perhaps the low salaries are a filtering mechanism that eliminates all but the most passionate and scientifically-driven applicants.

A pessimistic perspective, expressed by several sources for this report, is that the NIH intramural program employs mostly mediocre scientists. Talented scientists will take their big paychecks in the private sector, they say, or opt for the prestige of universities over the NIH.

Federal Employee Regulations

NIH researchers are federal employees. With that title comes regulations and overhead:

Employees must give six months notice for any business travel (such as going to a medical conference, giving a presentation at a university, and so forth).

All business travel must be coordinated through a government agency if the researcher wants reimbursement. This is convenient for NIH employees since the agency buys the tickets and automatically reimburses them, but due to some obscure regulation, the agency can only handle trips between the office location and one destination. This means that NIH employees can’t do multi-leg trips. If an employee wants to go to a conference in New York and then another one immediately afterwards in Boston, she must fly from Baltimore to New York, then back to Baltimore, and then to Boston.102

There are caps on many expenses, such as hotels. As a result, major conferences will often set aside cheaper, often overbooked hotel rooms for federal employees.

Federal employees need permission to attend “WAGs,” or widely attended gatherings. This includes basically any meeting, conference, or dinner where a private entity, like a pharmaceutical company, gives a material good to attendees (such as coffee and donuts). The approval process takes months, unless it’s a major event that has pre-approval.

Federal employees can’t apply for many private grants because their rules don’t align with federal regulations. For instance, a federal employee can’t get a grant that transfers any IP rights to the granting agency, because that violates federal rules that dictate IP rights to researchers.

Federal employees can’t take government-provided equipment out of the country (such as laptops).

Federal employees cannot accept gifts of more than $20. Conference swag is prohibited, then, unless an employee wants to try to calculate the value of a Pfizer coffee mug.

One interviewee referred to these regulations as “death by a thousand cuts.” He said that he basically never goes to sponsored dinners, never accepts gifts and never attends conference exhibits.

That same interviewee was sympathetic to the regulations, though, and said they were put in place to avoid conflicts of interest and avoid undue influence on federal employees by private entities. .

Detractors of Intramural NIH Research

While most interviewees were overwhelmingly positive about the NIH intramural programs, there are detractors.

Two sources said they knew of intramural researchers who did very little useful work because they were so bogged down in red tape and federal regulations, or said that the NIH failed to attract top-tier, highly motivated researchers because of low pay.

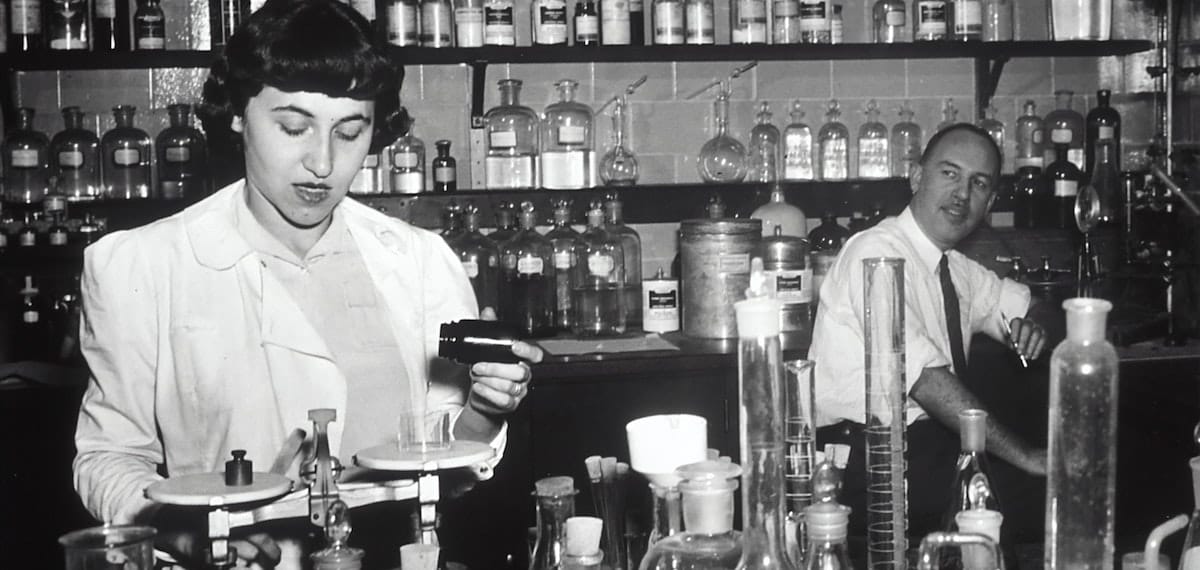

The NIH’s intramural system, said another source, had been the gold standard for scientific research in the 1950s and 60s, but has institutionally ossified. They claimed that the much-vaunted freedom of researchers was just as likely to produce laziness and coasting as brilliant scientific breakthroughs.

And, indeed, the NIH is uncharacteristically opaque about intramural research. Every extramural grant is extensively detailed (recipients, institutions, monetary amount, description, and so forth) on the NIH’s RePORT website, but there is no comparable database for intramural research. Thus, it is nearly impossible to evaluate the intramural program’s success, at least for outsiders.