Part 4: Extramural Research

How Study Sections Work

While researching this report, study sections – the peer review bodies that decide which extramural grants receive funding – swiftly emerged as peoples’ most hated topic related to the NIH.

The core complaint is that study sections have an incentive problem; there simply isn’t a reason for study sections to fund the best research.

Compare the NIH study section to comparable research evaluation groups at pharmaceutical or biotech companies. In the latter case, there are concrete goals: pharmaceutical companies fund research that leads to quantifiable financial or clinical outcomes. Companies that pick the right research topics will thrive; others will fail. Individual grant evaluators in these institutions are rewarded or punished accordingly through financial payouts.

NIH study sections have no output-based success metrics, nor are there rewards or punishments based on success or failure rates. Study sections are not disbanded if they make poor decisions.

To be clear: those that serve on study sections are not lazy or apathetic. Numerous interviewees emphasized a sense of scientific integrity, a genuine desire to fund the best research. But NIH study section reviewers are, first and foremost, fallible human scientists. They are prone to prioritizing those grant submissions that support their own research.

Some interviewees consider this lack of a reward system to be a feature, not a bug. The absence of clear metrics, they say, permits a more open consideration of research proposals.

But consider the problem in economic terms. Like the NIH, study sections have no competition, no means of evaluating success and no consequences for success or failure. Therefore, they lack reasons to tighten up waste and optimize efficiency. Scientific integrity can mitigate emerging structural problems, but the negative feedback conveyed by interviewees, as well as the current academic literature, indicate that it is not enough to prevent the system from drifting further into mediocrity.

Study Section Structure and Process

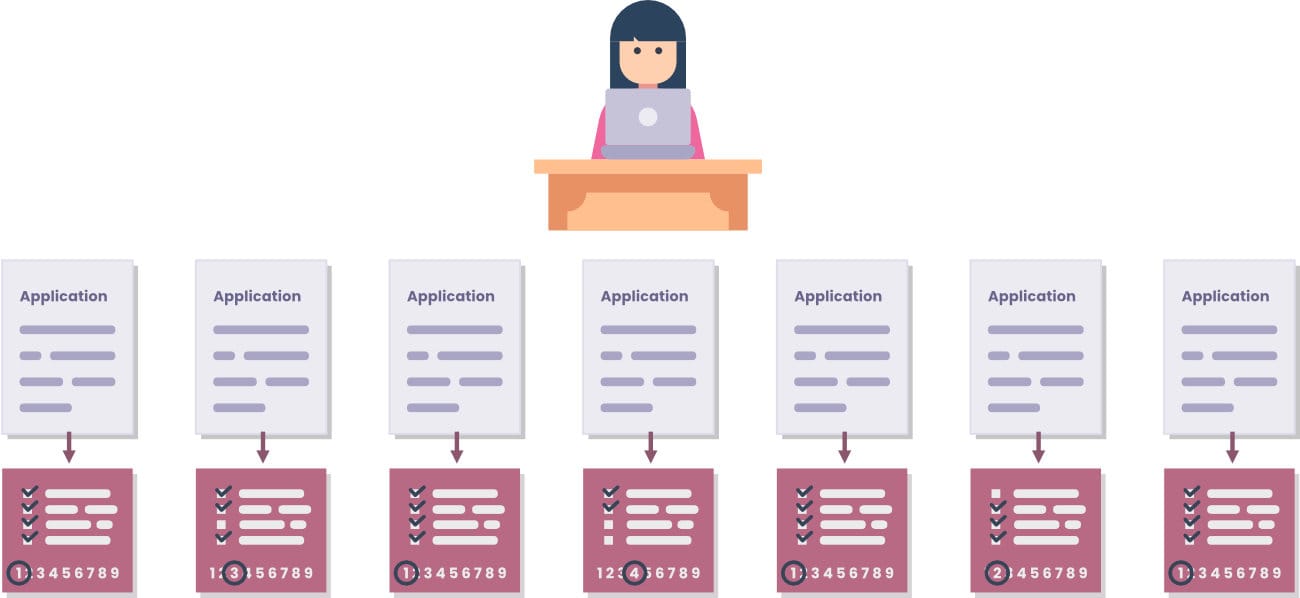

Study sections are run by Scientific Review Officers (SROs), established scientists hired by the NIH. The SROs appoint a team of 10 to 30 volunteer researchers, to serve as reviewers on their study sections. Each study section is focused on narrow domains within a given NIH institute.

About six weeks before a study section meeting, each reviewer is assigned (on average) 7 to 10 grant applications on which they are the primary or secondary reviewers. Each application has two or three primary reviewers. The reviewer assigns a score (1 to 9, 1 being the highest) to each of these applications, based on a rubric designed for the study section.

All reviewers can read the other 50-100 grant applications, though they aren’t expected to.66

The SRO and the appointed reviewers of study sections are public knowledge. However, the primary reviewers on each application are not public knowledge, so applicants are not supposed to know who their primary reviewers are (whether that’s the case in reality is debatable). The names, academic histories, and current institutions of each grant applicant are known to the reviewers. The NIH extramural grant evaluation process stresses an emphasis on the project proposals, not the research institution or past accomplishments. The degree to which this guideline is followed is also debatable.

Two to three days before the study section meeting, the SRO posts all the primary and secondary reviewer scores and written evaluations on a confidential website. All reviewers in the study section have access to this website. Applications in the bottom half of the score distribution are not normally discussed at the upcoming meeting, though individual reviewers have the prerogative to “rescue” these proposals and bring them up during the meeting.

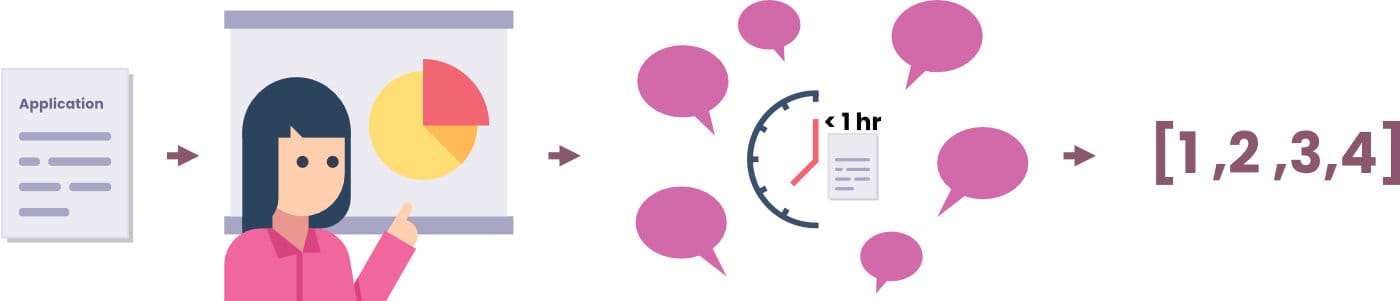

Study section meetings usually last two days, but can be done in one. The applications are evaluated one-at-a-time, and begin with the three primary reviewers giving five minute presentations. Then, the entire study section discusses the application for five minutes to an hour. With input from the primary and other reviewers, a score range is set by the SRO, and all reviewers submit a score.

The SRO writes up a summary of the evaluation for each grant, which includes the final averaged score. This score is converted to a percentile, and all applications below a certain percentile are funded. This percentile is known as the “pay-line,” and typically ranges from 15-30%.

Grant evaluations are sent to the applicants, but are not publicly available.

“Groupthink” and Other Issues

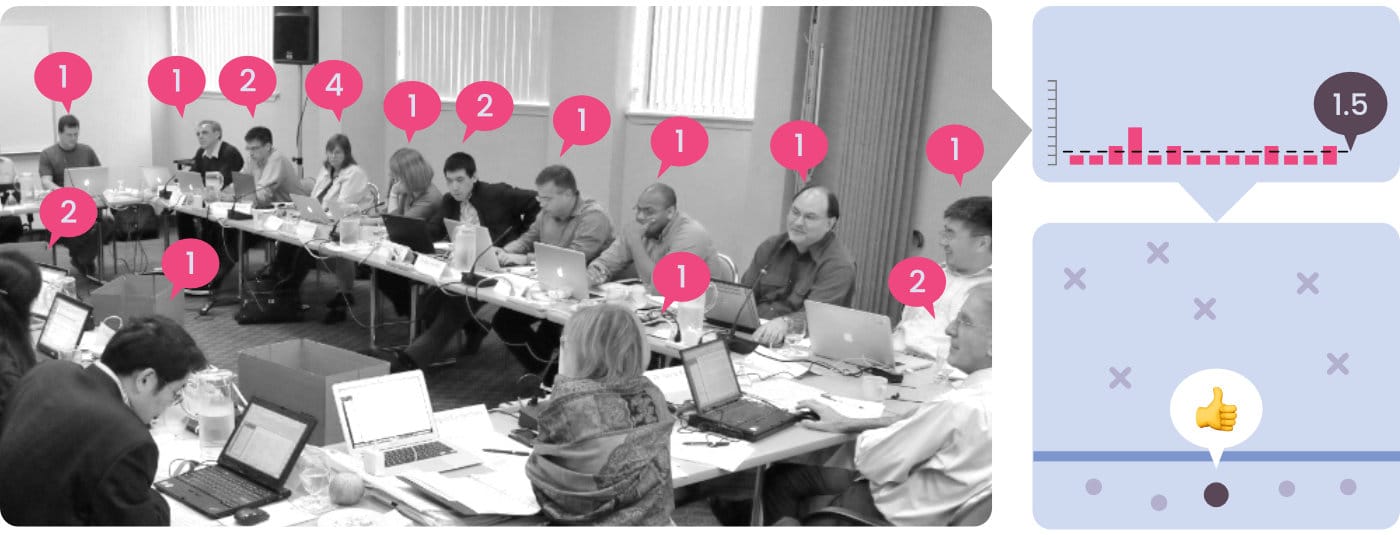

One of the recurring themes in interviewee descriptions, often explicitly stated, is that study sections tend to fall into “groupthink.” Theoretically, peer review panels are supposed to put independent voices together to argue different views until a consensus emerges, but often these groups of presumably highly intelligent and honest scientists succumb to group dynamics which prioritize conformity and conflict avoidance at the expense of objectivity.

The structure of the review process shoulders a lot of the blame. Recall: Roughly 10-30 scientists are given dozens, or even more than one hundred, grant applications to review. Each grant is assigned to two or three primary reviewers who lead the evaluation process.

Realistically, there are simply too many grant applications for everyone to read them all. Or in the words of one interviewee, “nobody wants to read all that shit.” Another interviewee admitted that they forced themselves to read all the grant proposals at their first study section, but then realized it was a waste of time and never did so again. Thus, most reviewers just read the applications that they will lead the discussions on, and then maybe skim a few others, or more commonly, read a few abstracts.

When it comes to voting on the other applications, most reviewers will naturally defer to the opinions of the two or three primary reviewers, thereby negating much of the value of gathering dozens of qualified scientists together for the peer review process in the first place. This establishes a consensus around each grant application which most reviewers rarely disrupt, whether out of a cost-benefit judgment that there’s nothing to gain by doing so, or out of apathy/laziness. One interviewee estimated that 90% of scores on a given application will be within 10% of the three principal interviewers' scores.

Numerous interviewees expressed frustration at this process, and felt like it was completely pointless to speak up for or against any grant application on which they weren’t the principal reviewers. One interviewee said that there is an unwritten rule that a reviewer can speak up for one, and only one, application that they’re not a primary reviewer on per session. If they speak up for more than one, they cross a social boundary and become that person who’s somewhere between an annoying do-gooder and boorish grandstander.

“If they speak up for more than one, they become that person who’s somewhere between an annoying do-gooder and boorish grandstander”

With so much evaluation power in the hands of two or three randomly chosen reviewers, lots of interviewees felt the study section process was highly arbitrary. If a grant happens to have a “charismatic” or forceful primary reviewer that likes the grant, its odds of approval go up considerably. One interviewee said they had seen mediocre grants get approval because an “alpha male” had basically bullied enough other reviewers. Other interviewees said they had seen good applications get shot down because their primary proponents were awkward, bad public speakers, or were non-native English speakers.

The conformity naturally induced by study sections is greatly amplified by what numerous interviewees called “politics.” Study sections are composed of experts in a single domain at various points in their careers. While this layering is intended to create multiple perspectives, it often leads to junior researchers deferring to senior researchers, either because they respect more experienced researchers, or because they are afraid of jeopardizing their careers by starting conflicts. More than one interviewee said they had seen blatantly mediocre grant applications get funding because everyone in the room was afraid to disagree with a prominent scientist. One interviewee claims that they were told in confidence by another reviewer that their application was torpedoed by a colleague who held a grudge. There is technically an appeals process for such issues, but it is considered cumbersome and unreliable.

An anonymous comment on an NIH article reflected the sentiments of the most negative interviewees: 67

“It is well known that NIH ‘confidentiality’ [of the primary reviewer to the grant applicant] is anything but, and a young PI risks career and reputation if they shoot down big names (not all, but there is a mafia of sorts). I’ve sat on panels, I’ve seen the influence from afar. Young PIs fall over themselves to get it good with the power brokers. I’ve seen young PIs threatened when they mentioned quietly that Big Boss X has data that is wrong. Some fields are worse than others, but it is overall a LOT uglier than most would believe.”

On the most nefarious end, a few reviewers mentioned, or implied, manipulation. Recall that study section reviewers are appointed by a Scientific Review Officer (SRO) who is hired by the NIH. The SRO can appoint pretty much whomever they want within basic qualification standards, so a few interviewees suggested that SROs are likely to appoint allies or lackeys, or dole out appointments as tokens of favor. Thus, the SRO might have enormous indirect influence over what sorts of applications are approved, even favoring some factions of research over others. One interviewee called this “turfism,” or the protecting of one’s research branch, and many other interviewees noted similar phenomena.

The most well-known example of turfism is the “Alzheimer’s Cabal.” As reported by STAT in 2019, for thirty years the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) was essentially captured by a faction of Alzheimer’s researchers who prioritized amyloid-based treatments and encouraged NINDS to avoid funding any other research pathways. One NINDS grant applicant related that a program officer “told me that I should at least collaborate with the amyloid people or I wouldn’t get any more NINDS grants.” Amyloid-based treatments for Alzheimer’s have come under heavy scrutiny over the last few years and the research field as a whole has drifted to more promising avenues.68

Granted, none of my interviewees mentioned anything as blatant as the Alzheimer’s Cabal, but they alluded to similar corrupt practices. One interviewee claims to have found “scams” whereby groups of researchers in particular fields purposefully wrote more grants to signal to the NIH that more funding was needed in that domain. The interviewee said this could be the result of a coordinated effort between the study sections and major researchers in the field, or it could be a decentralized trend that naturally emerges from the incentives.

Hearing these stories, I wondered how it was possible for an SRO to be so explicitly biased. There are at least two relevant failsafes in place: anonymous reviewing and SRO independence.

First, the study section process is theoretically anonymous since grant applicants can’t identify their primary reviewers, though the SRO and reviewers are public knowledge. But one interviewee said anonymous reviews are a “myth.” Though it violates NIH guidelines, reviewers can and do talk outside the confines of the review process, and primary reviewers can be identified if a grant applicant is so inclined to speak to the right people. After all, both the grant applicants and the reviewers are all in the same field, and likely know each other from conferences, papers, and general industry gossip. Petty grudges between individuals or factions can penetrate the allegedly anonymous review process, manifesting as blocked or artificially boosted grant applications.

Second, SROs are theoretically independent, and once appointed, are free to direct their review process however they see fit within limits. But the independence of SROs is at least questionable. One interviewee maintained that they genuinely are independent, much to the annoyance of NIH officers who wish they had more influence over loose cannon SROs. But another interviewee claimed that there was a lot more informal influence over SROs than is typically acknowledged. This could come in the form of the grant evaluation guidelines handed down to the SROs, or even from personal discussions behind closed doors between SROs and colleagues or NIH personnel. But again, no names were named, and it’s difficult to determine if such practices are widespread or occasional indiscretions.

One “No” is Enough to Kill a Grant

Grants that get funded are ultimately chosen by two or three scientists appointed by an SRO. The fickle, arbitrary nature of this process is readily apparent when compared to fundraising in the private sector.

Assume you have a startup company, and are looking for venture capital funding. There are hundreds of firms to choose from, and it’s a safe bet that you’ll be rejected by dozens of them (as many of the most successful startups are). A few firms will be true “believers,” though, and give you funding. The “reviewers” in this example are typically independent experts who make their living spotting and funding promising companies, rather than business people who run their own — potentially competing — companies in the field.

If you started a new supermarket chain, with the ambition of capturing a large part of the market, it’d be ludicrous if investments in your company were reviewed by Amazon, Walmart, and Target executives. Alas, this is precisely how NIH study sections work, whereby reviewers directly working in the field dictate grants for others and determine whether others will be able to enter and do work in that field.

Why do Researchers Serve on Study Sections?

Serving on a study section is not compulsory. Many of my interviewees complained about the time and effort required, and considered the process itself to be somewhere between badly flawed and farcical. So why do researchers choose to accept their appointments to study sections?

First, there is an implicit, professional obligation. Nearly all study section reviewers are current or former NIH grant recipients, and recipients are expected to serve. To my knowledge, there are no explicit mechanisms for punishing researchers if they receive a grant and choose not to serve, but I assume it would be frowned upon.

Second, it’s a great networking opportunity. Researchers meet and mingle both during the review process and outside working hours.

Third, it’s a good way to keep up with the current state of research in one’s domain. The submitted grants often indicate a field’s trends.

Fourth, nearly all interviewees noted that serving on a study section is the single best way to improve their own grant application odds. One interviewee said it was “extremely unclear” what reviewers were looking for until they served on a study section. Reviewers get to see the process from the inside, note guidelines, observe group dynamics, and therefore sharpen their own grant applications.

Fifth, it looks good on a resume.

Sixth, a few interviewees said they genuinely enjoy the process. Yes, there are a lot of headaches involved, but there can also be great discussions on the most important scientific issues of the day with brilliant people.

Application Response Times

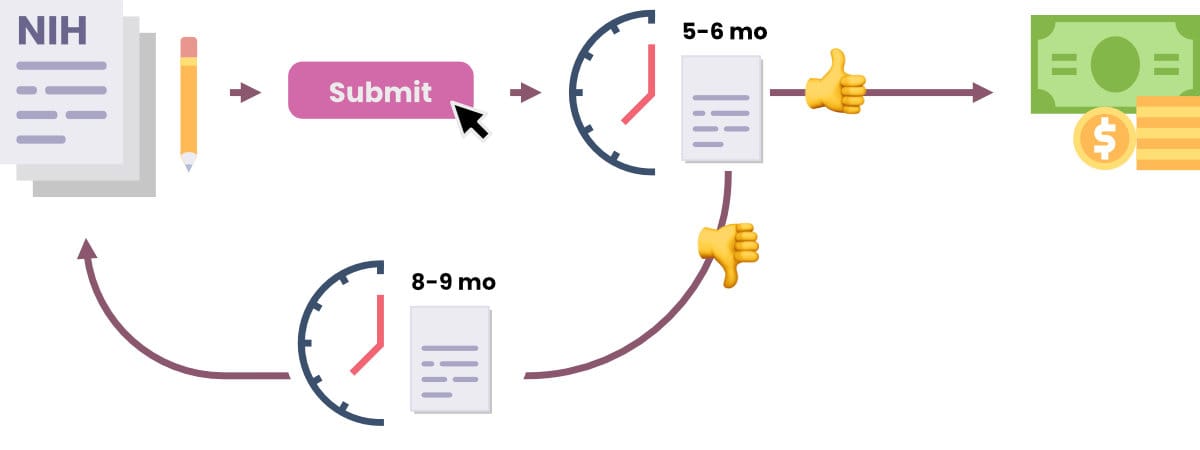

The final study section complaint is that the NIH takes too damn long to respond to grant applications. The standard wait-time for a grant response, as both noted by interviewees and online sources, is three months, followed by another few months before the money is distributed. Most institutions take half as long to process a grant. Interviewees attributed the long turn-around time to a multitude of bureaucratic measures, which one source summarized as “some government-y reasons.”

For many labs, the long turn-around time creates a treadmill effect whereby researchers have to carefully juggle multiple, concurrent grants and grant applications without accidentally leaving funding gaps. As one interviewee described it:

“A lab applies for an NIH grant. It waits 5-6 months from submission to get the final result, which is sometimes ambiguous and requires a few more months for acceptance or rejection. If rejected, the lab will want to resubmit the grant since with the feedback from the study section it’s easier to get an acceptance the second time. But the lab must wait “eight or nine” months before they are allowed to resubmit. Then once they resubmit, they need to wait another 5-6 months for a response.”

In sum, it can take 14 months before a grant submission results in funding. Meanwhile, existing grants will be running out. Postdocs will be coming and going from the lab. New discoveries will pull research in one direction while other research paths peter out. PIs will have to take all of this complex management and budgeting into account while going through a process which typically takes 6-14 months to pay out.

Proposed Reforms to Study Sections

Proposed improvements to NIH study sections vary widely. Each proposal could be elaborated upon, but I’ll stick to short summaries:

Professional Model: Some interviewees suggested transforming study sections into full-time review boards staffed by NIH employees. This model should insulate the peer review process from “political” concerns in the academic sphere, like interpersonal or factional conflicts. Two interviewees spoke favorably of their experience with pharmaceutical companies using this method, and another pointed to the Federal Drug Administration as a good model. Theoretically, the NIH could even devise some sort of incentive structure based on the Success Metrics for a professional study section to aim for, though all must be wary of Goodhart’s law.

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure” — Goodhart’s law.

Randomness: A few interviewees suggested injecting randomness into the grant evaluation process, through a variety of means. For one such proposal, consider the previous breakdown: 100 applications, 50 are mediocre, 30 are good, 20 are excellent, and 25 must be chosen. A study section could use its normal methods to filter out the 50 worst applications, then choose to award 25 of the remaining 50 applications at random. Or they could choose 12 of the remaining 50 by regular methods, and then choose 13 at random.

With decent Success Metrics in place, over time the NIH could even compare the outcomes of selected and random grantees and see who does better. Randomness could obviously lead to worse results, but it could also eliminate a lot of the pettiness and politics of the selection process.

Intramural Model: One interviewee suggested that researchers should go through the normal study section system for their first grant, but then go through the far more streamlined intramural system for grant renewals. This means that, rather than design proposals for grant renewals to be reviewed by study sections (a time-consuming process for all involved), the researcher could get a site visit and update NIH grant managers on their progress.

People Over Projects: A popular alternative among interviewees is to reorient the grant selection process around “people, not projects.” Currently, the study sections take grant proposals based on individual projects, but other research institutions, like the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), select applications primarily based on professional background and future potential. Supposedly, this system eliminates a lot of the minutiae which tends to amplify the bureaucratic processes of the NIH grant system.

Non-Academic Reviewers: One interviewee suggested that NIH study sections should be open to researchers from biotech and pharmaceutical companies. He blamed many of the study section errors on academic insularity, including a general risk-aversion. He claimed study sections are “biased against the very kind of research which is critical to the future of the enterprise.” Involving people from the private sector would also better connect the NIH to the marketplace and possibly push for more application-based research, though there is disagreement on whether this is a positive. At the very least, bringing in industry would likely add more dynamism to the overtly-academic setting. Another interviewee suggested mixing academic domains in the study sections to break factional strangleholds and make research proposals more broadly legible.

Give Grants to Institutions: Two interviewees suggested that, rather than give grants to researchers who are then supported by institutions, the NIH could give some or all grants to institutions or departments directly and then let them dole out the money. One interviewee was particularly concerned about the hierarchy within universities, though, wherein senior researchers controlled the grant money and had near-dictatorial powers over junior researchers. He suggested that by giving the institutions and the departments funding instead, there would be more oversight for this relationship and a fairer distribution of both funds and responsibility.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): The NIH could implement a variety of evaluative structures, let them run for an extended period of time (maybe 5-10 years), and then compare the results with Success Metrics.

In Defense of Study Sections

While all of my interviewees had critiques about study sections, a few were net-positive and made some good arguments.

One defended study sections by referencing the classic Winston Churchill quote: “It’s the worst form of peer review except for all the others that have been tried.” They argued that most of the flaws of study sections derive from the fact that they are run by humans who need to make judgment calls, and therefore there will always be such errors no matter how much the structures are tweaked.

“It’s the worst form of peer review except for all the others that have been tried.”

Another interviewee speculated that many of the harsher critics of study sections were probably researchers who had their proposals repeatedly shot down, and so they’re a bit like a struck-out baseball batter complaining about the umpire.

A third interviewee acknowledged the cronyism and politics of study sections, but said there was a strong cultural resentment of these practices which discouraged them. In their words, there is a “constant struggle, but one where science is prevailing.”

This sentiment was reflected by quite a few interviewees (both the net-negatives and positives). They claimed that the greatest strength of study sections was a genuine commitment to science and that, while mistakes are made and politics is a reality, most researchers are passionate about their work and want to fund the best projects possible. One interviewee said the “degree of [virtue] is incredible and exciting.”

Transparency of Funding Decisions

Perhaps the only universally-praised aspect of NIH study sections is their transparency. When study sections evaluate a grant application, whether approval is granted or not, their score and notes are given to the applicant. This gives the applicant information on how to improve their application for the next attempt, both in specific aspects that apply to their current project, and in general aspects that apply to future projects. Some interviewees noted that sometimes they disagreed with the feedback (or even found the reasons for their rejection irrational), but generally they considered the feedback immensely helpful. It’s also worth noting that the grant application processes at other institutions (non-profits, etc.) rarely give feedback like the NIH.

the grant application processes at other institutions (non-profits, etc.) rarely give [helpful] feedback like the NIH.

Grant Writing and Maintenance

A common complaint among extramural grantees is that the NIH’s grant application process is onerous, bureaucratic, and time-consuming. On the most extreme end, some interviewees said that grant applications and maintenance make up a substantial portion of their general work time and reduce their overall research capacity.

Grant Preparation

The time and effort commitment for NIH grant writing varies by institution. Some universities and research labs provide considerable administrative support to researchers, including full-time administrators who handle part of the application process, particularly for well-established researchers. The help provided by top-tier universities, then, further supports the incumbents.

Other institutions provide little-to-no support. When asked how long it takes to write an NIH grant proposal, the responses I got ranged from weeks to one month of full time work at the lowest end, to three months at the highest end. One survey of bioscience researchers found that 57% of respondents spent one quarter of their work time writing grants.69

For well-established labs with a decently large staff, it’s common to have professional grant-writers who do nothing but write grants year-round. After all, a large lab will juggle multiple concurrent grants, and will constantly have to apply for renewals and new grants. So, a significant portion of money and manpower intended for scientific work will be permanently diverted to asking for more money. In one extreme case, an interviewee claims to know of a lab that spent 50% of its man hours to this end.

Many interviewees referred to grants being filled with paperwork that had no bearing on their experiment. In one case, an interviewee said they wrote a grant with 24 pages of scientific designs and 76 pages of “planning and maintenance” forms.

In both the low and high estimates, the interviewees referred to grant writing as a full-time job. As in, 40 hour weeks of nothing but planning and writing, with little time for ongoing research or teaching. An NIH criticism written by former NIH Director Harold Varmus and others described the problem:

”…biomedical scientists are spending far too much of their time writing and revising grant applications and far too little thinking about science and conducting experiments… Today, time for reflection is a disappearing luxury for the scientific community. In addition to writing and revising grant applications and papers, scientists now contend with expanding regulatory requirements and government reporting on issues such as animal welfare, radiation safety, and human subjects protection. Although these are important aspects of running a safe and ethically grounded laboratory, these administrative tasks are taking up an ever-increasing fraction of the day and present serious obstacles to concentration on the scientific mission itself."70

Grant Maintenance

Once an NIH grant is attained, there are requirements for periodic reports to the NIH, which are generally referred to as “grant maintenance.” The burden of this grant maintenance falls to varying degrees on researchers and institution administrators, depending on both.

Generally, universities have a larger administrative staff, which can carry a smaller or larger percentage of the burden. Additionally, established researchers will generally get more support from the administrations or, failing that, use their grant money to hire full-time grant maintenance workers.

This is one area where the NIH gets a gold star. Its grant maintenance is considered minimal, and usually consists of just one or two reports per year. Most other institutions have more requirements.

The worst example I heard of was, surprisingly, DARPA, an agency which usually gets glowing reviews. Two interviewees with DARPA grants said they had to write numerous overlapping period reports (i.e. quarterly, annually, at certain benchmarks, etc.). In one absurd instance, they had multiple period reports fall on the same due date, but they still had to write the same exact information on multiple forms and submit them simultaneously.

“Grantsmanship”

Some interviewees described a process called “grantsmanship,” or the contouring of grants to meet NIH evaluation standards. Grantsmanship can be helpful, annoying, or actively harmful to science as a whole.

On the most helpful end, as already mentioned, grant applicants adjust their applications based on feedback they get from study sections after failed applications. Most of the time, this advice is genuinely good and makes their projects better.

In the annoying middle, applicants adjust their applications based on feedback in ways they consider arbitrary. Maybe they need to stress a factor in their experiment they don’t find meaningful, or adjust their formatting in a way that their particular study section prefers due to pointless NIH regulations.

In the arguably harmful middle, some researchers heavily pursue fads in research. At any given time, some research topics are more likely to get funding than others because they are more popular in the scientific or mainstream communities. Many interviewees brought this up, though there was disagreement over whether it’s a bad thing. At worst, chasing fads causes valuable long-term research priorities to be abandoned for the sake of increasing grant application success odds.

On the definitely harmful end, some interviewees believe that grant applications across the board are leaning into a variety of negative trends as applicants sacrifice grant quality for higher acceptance rates. The most commonly cited trend is toward conservatism, where applicants will prune their project’s aims, focus on concrete deliverables, and avoid open-ended questions more characteristic of basic science. Some interviewees believe this sentiment has infected nearly all grant applicants, especially younger ones, but plenty of other interviewees were less pessimistic.

On the most extreme end, one interviewee said, “there’s not an honest submission” anymore, because virtually all applicants will lie to some degree about their research goals. Either they will write an application for a project they don’t really want to do but will do anyway for career purposes, or they will write an essentially fake application and then secretly follow their own research designs.