Part 5: Indirect Costs

The NIH’s extramural grant system is somewhat convoluted, but it has a logic. It is designed to promote private research with government money while simultaneously fostering research institutions through subsidies.

When the NIH awards extramural grants to researchers, the funds are divided between direct costs and indirect costs.

Direct costs are funds given to the researcher. These funds cover costs that are easily associated with the researcher and their team, including salaries, supplies, equipment, and lab space.

Indirect costs are funds that the NIH gives to the hosting institution (e.g.. a university, hospital, biotech company, etc.). These funds cover costs incurred by the hosting institution which are not easily identifiable with individual researchers or projects, such as depreciation and debt on research buildings, equipment depreciation, and “operation maintenance” (e.g. utilities, repairs, janitors, etc.).71 The indirect cost rate is a fixed percentage negotiated between the hosting institution and the government which determines how grants are divided between direct and indirect costs.

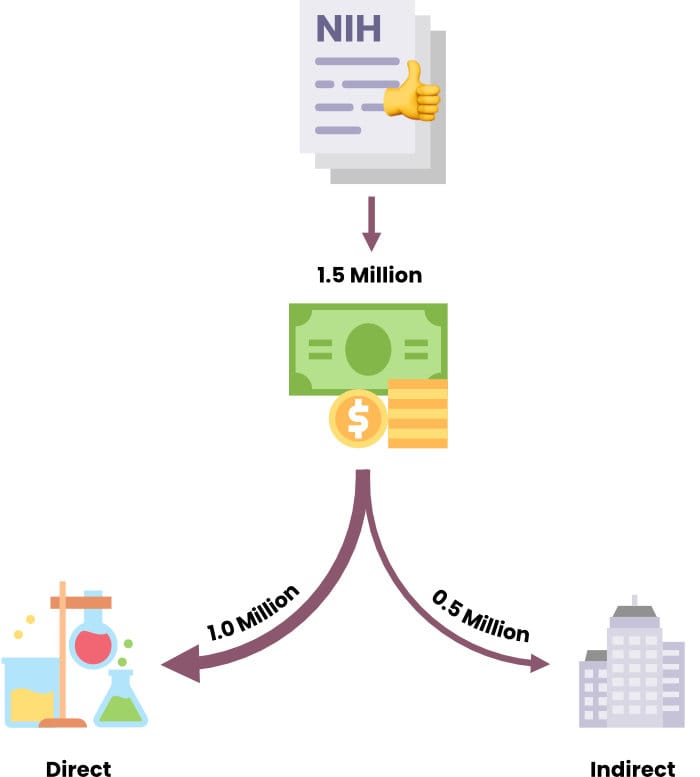

Consider a simple case: You are awarded a $1.5 million grant and your university’s indirect cost rate is 50%. Then, the NIH would send you $1 million to spend at your discretion, and another $500,000 directly to the university. (There are also some direct costs that don’t garner indirect costs, like equipment, so it’s usually a little more complicated to calculate.)

In 2017, the average standard institutional indirect cost rate was about 53%. In 2020, American universities earned about $8.1 billion in indirect costs. 72

Why are there indirect costs to begin with? Well, it’s because research — and especially bioscience research — is expensive. Universities house the researchers, give them lab space, give them equipment, manage them administratively, assist with grant applications, assist with networking, and shoulder a large share of total research costs. Without external funding, most federally funded researchers would be net-costs for the universities, and major research institutions couldn’t possibly employ as many researchers as they do today.

Most people that I spoke to for this report had criticisms of the indirect cost system, at least in its current form. One interviewee called the system “weird and inefficient.” Others called it “a complete rip-off” and “welfare for elite institutions.” At the most extreme end, others described it as a “scam” in which major universities with enormous endowments continually get taxpayer funding through an opaque and highly gameable system.

Less vocal interviewees said the NIH was probably overpaying many institutions through indirect costs and, at the very least, there is probably an incentive misalignment at play to the detriment of taxpayers.

Most people don’t know that top research universities earn a significant portion of their revenue from the government, ranging from about 10-30%. Most people also don’t know that their tax dollars are being used to fund expensive buildings and administrative staffs on campuses of universities with their own multi-billion dollar endowments. And most people don’t know that the flow of money from the government to these research universities has increased tremendously over the past thirty years, both due to the federal funding levels and the expansion of universities.

At the very least, there needs to be more scrutiny into the opaque, indirect cost system, and how universities attain and use government funds.

At its founding, the NIH and its predecessor institutions had no indirect costs. The NIH introduced the system in the 1950s on the grounds that large institutions with larger budgets were privileged since they were more easily able to sustain the administrative costs incurred by NIH grants. Initially, the indirect costs were capped at 8%, but soon rose to 20%. In 1965, the federal government began negotiating indirect costs with institutions. In 1991, the cap rose to 26% for administrative costs, but not for other indirect costs which remain uncapped.73

From 1967-1988, the share of NIH extramural spending on indirect costs increased from 17.1% to 32.6% (Note: A 50% indirect cost rate is equivalent to roughly 33.3% of the total grant going toward indirect costs).74 From 1998 to 2014, the share consistently hovered a little over 30%.75 By 2017, it had risen to one-third. In other words, about one-third of the NIH’s extramural budget, and almost 25% of its total budget, is being given directly to research institutions, primarily universities.76

In 2017, the average indirect cost rate was about 53%.77 However, individual rates vary considerably. Some examples (all on-campus, school year starting in 2020 or 2021 unless otherwise specified):

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2022) – 55.1%78

University of California Los Angeles (2019) – 56%79

Stanford University – 57.7%80

California Institute of Technology – 68.4%81

Harvard University – 69%82

Note that private research foundations generally have even higher indirect cost rates. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center is at 76%,83 the Salk Institute for Biological Studies is at 90%,84 and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory is at 92%.85

Some of the increasing indirect cost rates are partially to blame on the NIH because of its increasingly burdensome grant requirements. The process of writing and maintaining grants requires an entire university bureaucracy, which means more salaries, more benefits and more employees.

How are Indirect Cost Rates Calculated?

A common misconception is that indirect cost rates are calculated by the NIH. Rather, most indirect costs paid to organizations for research projects are calculated by one of two “cognizant agencies;” the Health and Human Services Division of Cost Allocation handles most science matters (including the NIH), while the Department of Defense’s Office of Naval Research handles military projects.

These agencies negotiate indirect cost rates every four years with all institutions that house federally funded researchers. Once a rate is set, it applies to all grants given by a particular federal agency to the institution.

Basically, the government tries to figure out what percentage of total research costs for a given grant will be shouldered by the institution. Then, when it crafts grant payments, it divides the funds between a direct payment to the researcher and a payment to their institution.

The “pool,” which represents the institution’s costs, is determined by a negotiation between the cognizant agencies and the receiving institution. For the sake of relevance and simplicity, I’ll assume the institution is a university for the following sections.

The pool is all administrative and facilities costs incurred by the university in connection to its federally-funded researchers. Recall that administration costs are capped at 26%, and facilities costs are uncapped.

Again, the basic premise of reimbursing institutions for shouldering some of the costs of federally-funded researchers makes sense. But with the current system, there’s a potential issue:

As the NIH’s own instructional video points out,86 an old research building on a university campus generates low depreciation and probably has no debt, so it yields few subsidies. Since debt and depreciation are “pool” costs, such a building yields few indirect cost subsidies. A new research building generates high depreciation and debt, so it garners large subsidies. Thus, universities can often construct expensive, new research buildings at relatively small cost to them.

There have been a few instances of high-profile, indirect cost fraud. In 1994, Stanford University agreed to repay the US Navy $3 million for inflated indirect costs, including expenditures on flowers for the university president’s home and depreciation on a yacht.87 In 2016, Columbia University settled a case with the government for $9.5 million after it admitted that administrators purposefully mislabeled 423 research grants as “on-campus” rather than “off-campus” to cash in on the significantly higher on-campus indirect cost rate (61% to 26%).88 In 2020, the Scripps Research Institute paid $10 million to settle a claim that it had used its NIH-funded researchers for non-federal research tasks, including “writing new grant applications, teaching, and engaging in other administrative activities."89

One interviewee, part of a lab at an elite research university that receives NIH funding, shared an anecdotal story about indirect costs. This particular researcher had a conflict with another research team, because that research team kept coming into their lab to take dry ice, without permission. My interviewee’s team contacted the university’s maintenance company (which is 100% owned by the university) and requested that they install a key card reader on the lab door to keep the other team out. The building had hundreds of these card readers already; surely, this was a cheap, simple request.

But the maintenance company told the research team that purchasing and installing the key card reader would cost over $10,000.

The interviewee then searched for the key card reader online and found one for $15. Installing and integrating the key card reader into the university system would add costs, but nowhere close to $9,985.

It’s impossible to entirely understand the accounting at play, but the logic is clear. When a university owns the maintenance company, that company can charge the university inflated prices. The university will be happy to pay because it gets all that money back through ownership, while shuffling its maintenance costs into its indirect costs, thereby garnering more subsidies from the federal government.

Are Universities Profiting from the Indirect Cost System?

They are almost certainly not directly profiting from indirect cost reimbursements, but they are almost certainly profiting through secondary benefits of federally-funded research and indirect costs.

In 2012, universities self-reported that they spent $13.7 billion of their own funds on research. Out of that figure, $8.9 billion was initiated by the university, either as self-funded research or as funding in conjunction with federally-funded research. That left $4.6 billion as “unrecovered indirect costs,” or money the university paid to support research initiated by external grants which was not reimbursed by the granter.

Though the source doesn’t break the figure down further, it could be disaggregated between grants from the NIH, other federal sources, and non-federal sources. At top schools, the NIH typically accounts for 40-60% of federal grant money, and non-federal sources account for less than 10% of all grant money, so we can make a ballpark estimate that universities paid around $2 billion out of pocket for NIH research. In 2012, all university research spending was about $66 billion, 90 and the NIH’s extramural budget was about $22.3 billion. 91

It should be noted that the initial $13.7 billion figure is outdated (from 2012) and is based on self-reporting, so it has not been independently verified.

But assuming the figure is accurate, it indicates that universities are losing money from NIH research, and maybe indirect cost rates should be raised.

However, a naïve view is that the universities are simply channeling government funding into scientific research. There are significant secondary effects and externalities at play. Those funds are about more than just research; federal funds cause universities to gain prestige, attract better faculty, and bring in more donations. This is where universities truly profit from federal research money and indirect costs.

These indirect cost payments should be thought of as a subsidy. The universities are not contractors bidding to provide a service to the government (though the NIH does do a small amount of contracting). Rather, universities are generating their own research through their employees, and the NIH is providing the funding, which is only bounded by the skill of the university researchers in applying for grants and the capacity of the university to host them.

Because these subsidies scale to costs, universities are incentivized to keep increasing their costs, all the better to bring in more grants, boost their prestige, bring in better faculty and so forth, ad infinitum. Administrative costs are capped at 26%, so their scaling is controlled, but the facilities costs are uncapped.

We know that universities are responding to these incentives due to their revealed preferences. For instance, the rate at which universities created new biosciences doctorates perfectly conforms to the trends in NIH funding. In other words, as the NIH budget increased, universities built more research facilities and created more bioscience graduates, likely despite losing more money to indirect cost overflows. Clearly the secondary benefits were worth these costs.

Nearly everyone interviewed for this report supports increasing the NIH’s budget, but universities and their beneficiaries have a strong incentive to promote and expand the NIH.

On the other end of the equation, there is little incentive to restrict NIH expenditure, nor to keep careful track of its funds, since the federal agencies that set indirect cost rates are largely unknown to the general public, and suffer from similar incentive problems. The Department of Defense’s Office of Naval Research is unlikely to suffer repercussions if a university inflates its official facilities expenditures with fraudulent purchases.

I am not suggesting anything nefarious; but the current structure does align incentives of the NIH and large universities.

As an example, here are the budgets of five major NIH grant recipient universities, and the fraction of federal funds that comprise their total budget. In all of these cases, NIH grants account for approximately 40-60% of the university’s federal revenue.

The [University of California San Francisco] received $771 million in federal grants and contracts in 2019 out of $7.6 billion in total revenue; that’s 10% of the budget.92

[Harvard University] generated 11% of its revenue from federally-sponsored grants in 2020.93

[Yale University] received $618 million in federal grants and contracts in 2020 out of $4.3 billion in total revenue; that’s 14% of the budget.94

The [University of North Carolina Chapel Hill] received $722 million in federal grants and contracts in 2020 out of $2.2 billion in total revenue; that’s 33% of the budget. Additionally, the NIH was UNC’s single largest source of funding at $523 million, or 24% of total revenue.95

[Johns Hopkins University] received $2.5 billion in federal grants and contracts in 2019 out of $6.4 billion in total revenue; that’s 39% of the budget.96 97

Recall, however, that those research institutions with the highest indirect costs are private; the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has 76% indirect costs; it’s 90% and 92% for the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, respectively. These high, indirect cost rates support the notion that universities do subsidize research out of their own pockets, and might be doing so to a great extent.

Are Indirect Cost Rates Too Low?

In 2017, Peter Thiel met with NIH Direct Francis Collins to discuss possible reforms. Thiel identified rising indirect cost rates as an issue, and suggested caps. In an email exchange after the meeting, Collins said he was sympathetic to reform measures, but defended the foundations of the indirect cost system:

“Universities complain that NIH’s indirect cost rates don’t actually cover all the costs, and they have to make up for that with tuition, donations, state funds (if they have any), and endowment funds. In 2012, the Council on Government Relations (COGR) estimated that institutions put $13.7 billion of their own funds into subsidizing research.”

The $13.7 billion figure refers to institutional funds, or all the money universities spend on research. Those funds are composed from institutionally financed research, cost sharing, and unrecovered indirect costs.

Out of the $13.7 billion universities spent on research in 2012, $8.9 billion is university-initiated spending that does not subsidize federally-funded research, while about $4.6 billion is accounted for as the “unrecovered indirect costs.” This is the amount of money universities report as spending on subsidizing all federal (not just the NIH) research.

Impact of Indirect Costs on Researchers

Recall that the federal, indirect cost rate for top research universities varies between about 50% and 80%. This creates a strong incentive for universities to encourage their researchers to pursue specifically NIH grants.

Entire training seminars for grant applications, according to interviewees, were oriented around the NIH. Getting a few NIH grants is generally considered to be a requirement for promotion and tenure. Researchers can and do apply for other grants, but the default assumption is that university bioscience researchers should apply for NIH grants, as opposed to grants from non-profits which pay far lower indirect cost rates.s.

However, NIH grants may be preferred simply because they are the easiest ways for researchers to get lots of money. As mentioned, it’s nearly impossible for bioscience labs to run on non-profit grants outside of a select few sources, like HHMI.

On the other hand, there is definitely evidence that university administrators are motivated by indirect cost rates. In the most severe cases, some universities levy a “tax” on researchers for obtaining grants from non-NIH sources. In the case of Columbia University, the tax is equal to the NIH indirect cost rate minus the other institution’s indirect cost rate. That percentage is taken out of the researcher’s direct costs. This policy dramatically diminishes the value of non-NIH grants.

For example, if a Columbia University (62.5% NIH indirect cost rate) researcher receives a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (10% indirect rate), with a direct cost of $1 million and a total value of $1.1 million, a whopping $525,000 intended for the researcher is redirected to the university, bringing the direct cost benefits to the researcher down from $1 million to $475,000. And frankly, that’s underselling the transfer, because non-profit grants tend to be much smaller than NIH grants; once the tax is paid, the remaining money might not even be worth applying for.

Slush Funds and Aggregations

There’s a quirk in the indirect cost system that makes it either more fair, or more distortionary, for certain universities. There is, in effect, a secondary cost layer embedded within the indirect costs.

It works like this: Universities receive lump sums of cash from the indirect costs paid by the NIH upon the disbursement of a grant to a university researcher. The university administrators then divide the funds between two categories of costs: fixed and discretionary. A portion of the funds go toward building depreciation, electricity, maintenance, and any long-term, fixed costs. Another portion of the cash is spent at the discretion of administrators on laboratories, according to their needs.

That second category resembles direct costs, except the funds are controlled by administrators, rather than researchers. The administrators might buy equipment for an individual lab, shift administrative resources for grant writing, or even refund some of the indirect costs back to the researcher.

If this system works effectively, then it could be a very strong safeguard against distortionary effects of the indirect cost system. Consider:

If no money was spent on discretionary, indirect costs, labs that spend less money would effectively be subsidizing labs that spend more money. All bioscience labs at a given university, after all, pay the same NIH indirect cost rate, regardless of how much equipment, electricity and maintenance they use. For instance, depreciation and debt on research buildings are indirect costs, so smaller research teams indirectly pay for a disproportionately larger share of the building debt and depreciation.

I initially assumed that the indirect cost system would tend to benefit experienced researchers at the expense of inexperienced researchers, since the former typically has more funding, larger labs, and uses more equipment. But the opposite might be more common.

Universities often spend huge sums on labs, equipment, or “cores” designed for common use to attract new researchers, while older researchers are left with older labs. Also, one interviewee claimed there administrators tend to provide more support to lesser-funded researchers with indirect costs, while better-funded labs are expected to take care of themselves.

This second example reveals a key factor in this secondary cost layer. How well this layer works is highly dependent upon the skill and objectivity of university administrators. Good university administrators could shift indirect cost benefits in a manner commensurate with each researchers' resource consumption. Bad administrators could fail to line up the costs and benefits, or worse, shift the benefits in an arbitrary manner, perhaps to support particular researchers for non-scientific reasons, like university politics.

Unfortunately, I did not get the opportunity to study this aspect of the indirect cost system in-depth. The wise dispersion of indirect costs within universities could be widely sound, corrupt, or highly variable by university. For what it’s worth, the interviewee who knew the most about this spoke highly of the administrators he knew at multiple universities.

How Do Indirect Costs Affect University Hiring?

Because of indirect costs, universities view researchers as grant-generating machines. At least from a financial standpoint, their value to the university is measured in how much money they can pull in. Output, or research quality, can impact prestige or maybe fundraising, but it is relatively devalued compared to the funds brought in by awarded grants.

Universities pass this incentive along to their faculty. Researchers are under immense pressure to generate grants; failure to do so puts their job at risk.

This could have a strong, negative effect on the tenor of university research. I’m sure faculty want to do good work, but they probably want to keep their job more. So most university researchers will sacrifice research quality for higher odds of grant acceptance and guaranteed funding.

Potential Reforms

In his email with Peter Thiel, NIH Director Francis Collins discussed potential reforms for indirect costs and claimed that eliminating indirect costs entirely would have “devastating consequences.”

Specifically, “American bioscience would take a giant step back,” as most research universities would close down, the rest would drastically cut their operations, and research diversity would plummet as a handful of surviving institutions would absorb NIH funding.

Collins then considered a 20% flat indirect cost rate, but said it would have “major negative effects.” He suggested 40% would be better, but still quite bad, especially because it would penalize specialized, private research institutions that tend to have high indirect cost rates (80%+).

Collins’s favored reform proposal, at least in this email chain, would be to reduce all current indirect costs rates by 5% (so a 50% rate would go down to 47.5%). Collins stated that this would cause institutions to “tighten their administrative belts” without serious issue, and would free up quite a bit of NIH money.